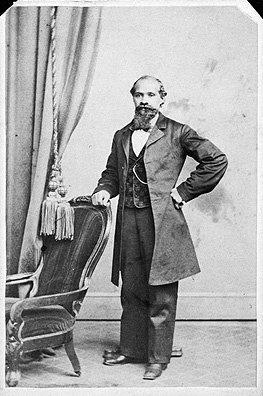

Colonel John McKee

Of African-American heritage, John McKee, was born in Alexandria, Virginia. He was apprenticed at a brickyard, but at age 17, he ran away to Baltimore where his uncle found him and brought him home to finish that apprenticeship. He then left for Philadelphia where he first worked in a livery stable, then at a restaurant on Market Street below Eighth Street. He married the restaurant owner’s daughter, Emeline Prosser, sometime before 1847 and operated the restaurant and dabbled in real estate until 1866, when he turned to investing in real estate full time.

Colonel McKee, was associated with the 12th and then the 13th Regiment of the Pennsylvania National Guard as well as the 8th New Jersey in the early 1870s, both as an organizer and an officer.

When he died of a paralytic stroke on April 6, 1902, at the age of 81, he was called “the wealthiest negro in the United States” according to an article in the New York Times (April 11, 1902). His estate included extensive mineral and real estate holdings in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Georgia. McKee City, in Atlantic County, New Jersey, was created by him from what was a wilderness in the “Pine Barrens.” He also owned over 300 rental properties in Philadelphia and a personal residence at 1030 Lombard Street.

After numerous provisions for his friends and family, John McKee’s Will directed that the balance of his estate be held in trust for the purpose of establishing a college, with emphasis on nautical training and a curriculum similar to the United States Naval Academy. The school was to be for “poor colored male orphan children and poor white male orphan children (and by the term ‘orphan’ I mean fatherless children)” between the ages of twelve and eighteen years. Included in his estate was sixty-six acres of land along the Delaware River that would have been an ideal site for such a school. He set forth many other details of its proposed operation in the Will, which was probated on May 21, 1902.

Although not raised a Roman Catholic, Colonel McKee named the Archbishop of Philadelphia and his own attorney, Judge Joseph P. McCullen, as executors and trustees of his estate. It is understood that he had confidence in the continuity and integrity of the Catholic Church, stemming largely from the fact that, when he was stricken with typhoid fever in 1896, he found that Catholic nuns would minister to him and other persons of color suffering from the disease, while many other white caregivers would not. The Archbishop of Philadelphia is presently the sole trustee. The trust benefits fatherless boys of all faiths and races.

According to contemporary accounts, Colonel McKee was buried from the Central Presbyterian Church, then located at 9th and Lombard Streets, Philadelphia, rather than being buried with his wife in the Lebanon Cemetery as stipulated in his Will. It is reported that he was laid to rest at the Olive Cemetery, 46th and Merion, Philadelphia. His Will was not read until after his funeral, so his detailed funeral instructions were not followed. Both cemeteries were later closed and his and his wife’s remains were moved to Eden Cemetery, Collingdale, PA, in or about 1923.

When time came to set up McKee College, a “lost” heir by the name of T. John McKee and some existing schools claimed that, since the estate was then inadequate to establish a new institution in accordance with the exact terms of the Will, the fund should be paid to him or to them. The heirs argued for an intestacy; the schools asked that the estate go to one of them. After years of litigation, the Court issued anOpinion, based in part on the Preliminary Report of Amicus Curiae and theRecommendations of the Master, that, since the purposes of the Will could not be fulfilled precisely as Colonel McKee had specified, the estate should be used for the purpose most nearly approximating Colonel McKee’s educational goals until the fund might be sufficiently increased, by further donations or otherwise, to endow the school that he envisioned. Until that time, in the view of the Court, the trust should provide current educational assistance in the form of post-secondary college and vocational scholarships to fatherless young men of all races from the five county Philadelphia area in Pennsylvania. While the fund has grown, the costs of building and endowing the school he planned have risen even more. So this Trust continues to grant scholarships and receive contributions from supporters of Col. McKee’s vision.

In 1955, the John McKee Scholarships were established to assist applicants who meet the conditions set by the Court under the Will. A Committee of distinguished citizens was chosen by the Court to administer the selection process and to establish criteria for the awards. It has been possible, through these scholarships, to aid hundreds of fatherless young men, providing them the means to pursue further education, both at the college level and by way of vocational training, and, thus, to honor the charitable intent of Colonel McKee.

Click here to view the John McKee Archives.

John McKee’s connection to George Washington

George Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, the widow of Daniel Parke Custis. Daniel and Martha had had a son, John Parke “Jacky” Custis and he had a son, George Washington Parke Custis, known as “Wash”, who was adopted by George. As a result, Wash became George’s grandson, by adoption. Wash had a daughter by a slave, Arianna Carter, by the name of Maria Carter Custis (George’s great-grandaughter). She married Charles Syphax and they had a son, Douglass P. Syphax (George’s great-great-grandson). Douglass married Abbie Ann McKee, the daughter of John McKee. So John McKee became the father-in-law of George Washington’s great-great-grandson! (By the way, George Washington Parke Custis (Wash) married Mary Fitzhugh and their daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis married her third cousin, Robert E. Lee!)

Pingback: 400 years of black giving: From the days of slavery to the 2019 Morehouse graduation – The Daily Angle

Pingback: 400 Years of Black Giving: From the Days of Slavery to the 2019 Morehouse Graduation – Atlanta Tribune